Turquoise - Encyclopedia

Turquoise - Encyclopedia

Class : Phosphates, arsenates, vanadates

Subclass : Hydrated phosphates

Crystal system : Triclinic

Chemistry : CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)84H2O

Rarity : Uncommon

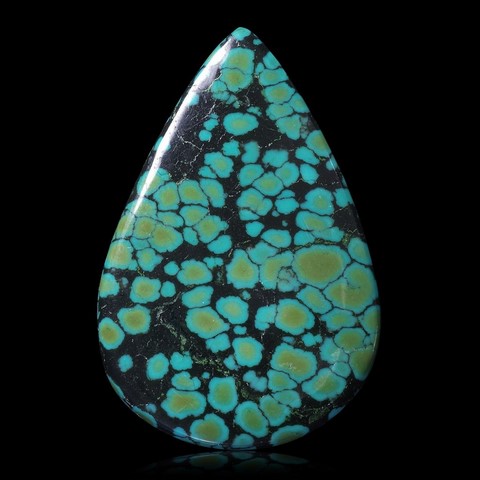

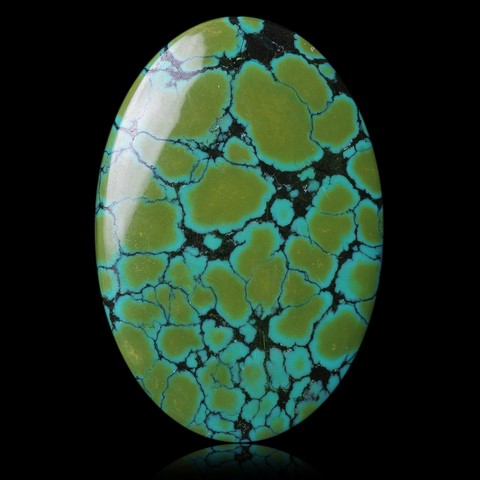

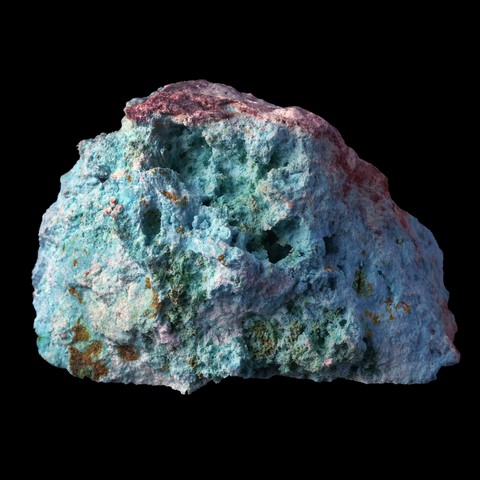

Turquoise is a secondary hydrated phosphate appearing mainly by alteration of aluminous rocks or primary phosphates (amblygonite) in arid climate. Since copper is essential for its formation, turquoise is found near large deposits of this metal, such as copper porphyries (the case of Iranian deposits and certain American deposits). Turquoise forms a continuous series with chalcosiderite, in which aluminum is substituted by Fe3+. This mineral was so named because it was exported from Persia to Europe by Turkey. It is practically known only in nodules (sometimes several tens of kilos), of waxy luster, apparently amorphous, but revealing itself to be cryptocrystalline under the microscope with a porous structure and retaining water. Its crystals are exceptional and millimetric for the bigger ones. Sky blue to greenish blue ("turquoise color") sometimes apple-green in color, turquoise tends to tarnish, particularly in nodules exposed to dry air. It is a stone of major economic importance, it is both mined as copper ore in several American deposits (Nevada and Arizona), and it is also a mineral widely used in jewelry for its magnificent color.

Turquoise in the World

Turquoise in France

In France, there are small masses of turquoise in alteration of amblygonite in Montebras (Creuse, France). We also find turquoise in the quarries of kaolin of Echassières in coating and in small millimetric green balls.

Twinning and special crystallization

Turquoise, on the other hand, can totally or partially replace fossil organisms. The Potosi Mountain deposit in Nevada (USA) revealed fossil bones of Pleistocene mammals partially and completely transformed into turquoise like this spectacular jaw in its matrix on the right (© Rob Lavinsky & irocks.com).

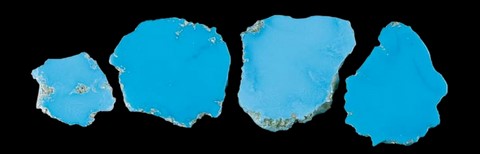

The many treatments of turquoise

In the world of jewelry, the porosity of natural turquoise is generally a threat to its stability. This porosity also allows him to easily accept the treatments. They can make the "turquoise" color more stable by isolating foreign substances such as cosmetics, perspiration and fatty substances. Exposure to heat and sun can also damage the color of some untreated turquoise. Until fairly recently, the most common treatment for turquoises was to dip the stone in melted wax. The wax then seeps into the pores. The wax was generally colorless and the treatment relatively stable. Currently, colorless oil or polymeric plastic is used to replace wax. Impregnated turquoise is defined commercially as "stabilized", almost all turquoises are treated. The photo above (© Maha DeMaggio) shows a series of turquoises impregnated from Sleeping Beauty (Arizona), only the sample on the left is untreated. Dyed turquoise is not very common, probably because the results seem unnatural and the treatment is not stable. Sometimes the turquoise is dyed with black shoe polish in patterns that try to imitate the matrix.

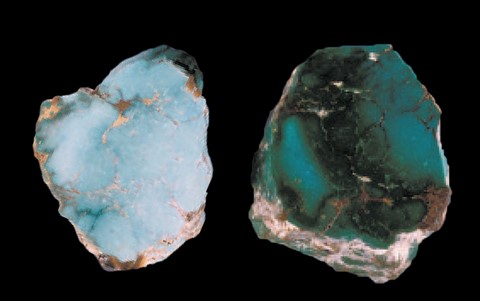

Other treatments include applying epoxy to thin slices of turquoise to consolidate and darken them. This new treatment, known as the "Zachery method", appeared in the late 80's, and has been used to treat more than 10 million carats of turquoise since then... Gemstone emerge from the treatment with a better color, lower porosity and the ability to take better polish. To date, treatment has been shown to be stable and has not disappeared over time. The photo opposite (© Maha Tannous / GIA) shows a turquoise cut in half, the left part has not been treated while the right part has been treated with the Zachery method. The details of this method are somewhat mysterious. Even the business owner claims not to know what's going on during the treatment... Gemologists aren't sure what causes the color enhancement. In tests conducted by the GIA, most turquoises treated with the Zachery method have been found to contain much more potassium than untreated natural ones. The cause of this difference is unknown... However there are a few subtle features that may indicate the possibility of Zachery treatment. Zachery treated turquoise sometimes has a concentration of color in and around its fractures. Its color, a pretty Robin Egg Blue, may appear slightly unnatural. Zachery treated turquoise can be detected by soaking it in an oxalic acid solution, but this test is destructive because it whitens the color. The best way to know for certain if a turquoise has been treated with this method is to send it to a gemology laboratory.

Fake turquoise

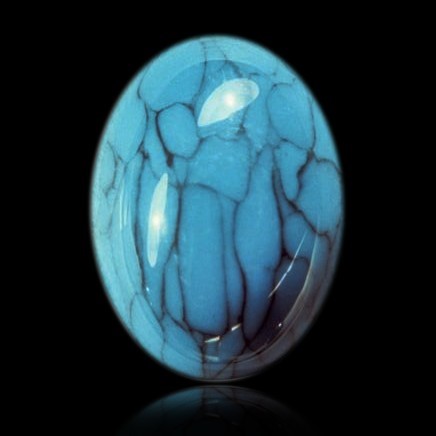

As a rule, when a gem material is abundant, manufacturers do not make much effort to synthesize it. Unless the stone in superior quality is rare and there is a demand... This is what happened in the 1970's. This is why the Gilson company, creator of other synthetic gems, introduced Gilson synthetic turquoise in the 1980's. Synthetic material, produced by a ceramic method, has never been widely available. Its appearance is semi-translucent to opaque, a light blue to medium color, often with an anthracite gray matrix of artificial appearance which resembles the pattern of a spider web.

Imitations of turquoise in glass and plastic are quite common. Plastic is particularly common. The Fimo paste commonly sold in the supplies of hobby shops takes a polish similar to that of turquoise and is very easy to work. It also costs very little... The temptation to deceive can be high and the result is very convincing.

Another type of false turquoise is the so-called reconstituted (or reconstructed) turquoise. The name is misleading because these stones often do not contain turquoise at all. It is a mixture of powdered minerals, dyed and bonded with plastic or epoxy resin. In addition to artificial imitations, some natural materials may look like turquoise enough to serve as alternatives. Howlite (magnesite), a semi-translucent white to opaque mineral with a dark gray or black veined matrix. When the material is dyed blue, it looks like turquoise.

Turquoise-like stones

Variscite is a translucent to opaque mineral mainly found in the United States, which varies from light green to yellowish green and bluish green. It looks so much like turquoise which is sometimes called turquoise from Nevada or California. The occasional marking of the yellow to brown matrix of variscite increases its resemblance to turquoise. The availability of the stone is limited.

A blue variety of chalcedony, colored by chrysocolla, can also strongly resemble turquoise. However it is translucent to semi-translucent, this American jewel is an intense light blue to blue green. Like variscite, its availability is limited.

Hardness : 5 to 6

Density : 2.6 to 2.9

Fracture : Irregular to sub-conchoidal

Streak : Green-blue, white

TP : Opaque

IR : 1.610 to 1.650

Birefringence : 0.040

Optical character : Biaxial +

Pleochroism : Not observable

Fluorescence : None

Solubility : Hydrochloric acid

Magnetism : None

Radioactivity : None