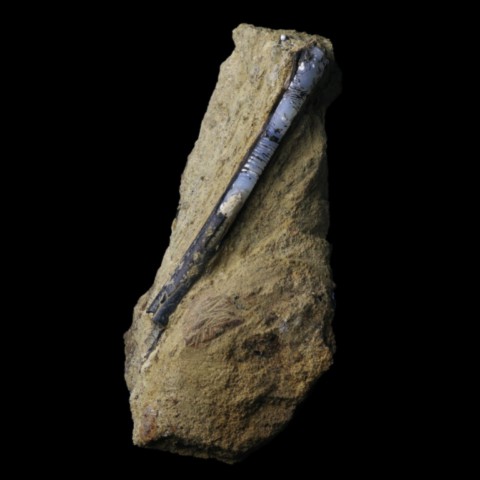

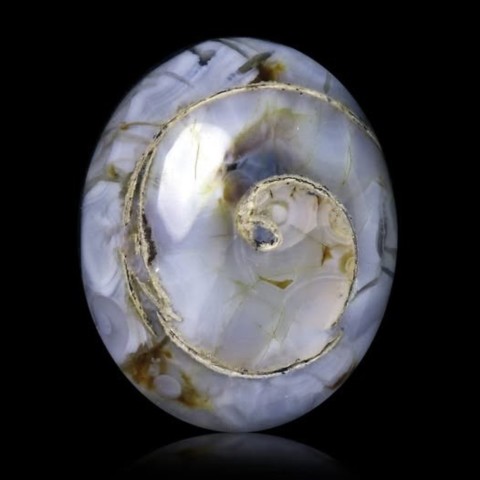

Paleo-snails in lussatite from Dallet - France

In the vicinity of Dallet, a small town nestled in the Puy-de-Dôme, in the heart of the Limagne plain, a paleontological and mineralogical treasure fascinates researchers and enthusiasts : epigenized fossils in lussatite. These specimens, particularly gastropods, offer a unique insight into the interactions between biology, geology and volcanic activity several million years ago...

Photo on the right : Epigenized Helix ramondi in blueish lussatite from Dallet, Puy-de-Dôme, France

Badgers' first discoveries

During the winter of 1998, while the vegetation was lying down under the weight of the frost, a rock outcropping near the Colombier des Rois mine caught the attention of an enthusiast : Mikael Boullot. He then came across intriguing hummocky concretions. Among them, a fossilized snail in blueish lussatite. However, the first discovery of a complete specimen, although precious, was too fragile to be extracted. This moment marked the beginning of a passionate quest, which would last for years... Depicted by Alfred Lacroix in 1901 in the famous "Minéralogie de la France et de ses colonies", present in the old collections of the Lecoq Museum in Clermont-Ferrand, these lussatite fossils were considered the Holy Grail to have absolutely in a collection! But it would not be until a few years later, in 2009, that an unexpected chance would accelerate the discoveries. Marc Henry, helped by Mikael's indications, discover new fossils. He locates galleries dug by badgers near the first discovery site. The debris left by these animals reveals magnificent specimens of fossilized helix, littering the slope of a small cliff. After several unsuccessful attempts to locate the fossiliferous layer, it was only a year later that a "nest" of lussatite fossils was discovered, containing an astonishing variety of species including planorbes, limnea and even bones. The layer will then be exploited for 3 days and then the site restored.

Geological conditions : the work of volcanism

The lussatite fossils of Dallet are the result of a unique geological context. During the Oligocene and the beginning of the Miocene, the Limagne limestones were subjected to intense hydrothermalism caused by volcanic activity. Waters enriched in silica following their percolation in the siliceous volcanic materials, infiltrated through the cracks in the limestone rocks. The lussatite then crystallizes in the empty spaces of the rocks which are mainly the empty shells of fossil gastropods or bioturbations (small burrows, root holes, etc.), more rarely inside hollow bones of palaelodus (ancestor of the flamingo). Bitumen facilitates these replacements, because being impermeable it accentuates the concentration of silica in specific areas. This process gave rise to these shells filled with lussatite, often accentuated by the presence of black bitumen. While most of the shells discovered belong to terrestrial species, such as Helix ramondi, some have aquatic morphologies typical of planorbia or limnea. These gastropods lived in shallow marshes, evidence of a rich but unstable environment.

A mineralogical treasure : the diversity of deposits

The Dallet region is home to several deposits where these fossils have been found. Among the most famous sites are :

The Champs des Poix mine in Pont-du-Château : famous for its white lussatite specimens.

The Colombier des Rois mine : known for its epigenies that are rarely complete, but often associated with quartz crystals.

The slopes above Colombier : offering the most beautiful blue specimens, often accompanied by brown and white chalcedony.

Each site tells a different geological story, reflecting the nuances of epigenization processes and local variations in volcanic deposits. These sites are all inaccessible today, the old bitumen mines are closed and the slopes of Colombier are subject to a municipal decree prohibiting mining after the looting and partial destruction of the site.

Scientific attribution: Helix ramondi or Helix moroguesi ?

The Dallet snail fossils raise complex questions about their classification. Historically, they have been attributed to Helix ramondi, a species described in 1810 by Alexandre Brongniart and very present in the nearby Mine des Rois. However, their anatomical characteristics, often altered by epigenization, make this identification uncertain. Some paleontologists suggest that they could belong to another species of Helicidae, or even to Helix moroguesi.

These discussions illustrate the challenges posed by transformed fossils. While epigenization has magnified these shells aesthetically, it has also erased details crucial for precise classification. Indeed, most lussatite snails are internal molds, the shell and its ornamentation have completely disappeared.

A mystery to solve: shells in "life position"

One of the most intriguing phenomena observed at Dallet is the arrangement of the fossil shells. These are overwhelmingly aligned in what appears to be their life position, with the apex pointing upwards, which has sparked heated debates about a possible mass mortality. These snails, fossilized in dense and homogeneous groups, seem to have been frozen in a precise moment of their existence, suggesting a catastrophic event. Several hypotheses attempt to explain this phenomenon.

Hypothesis 1: A sudden rise in water levels

The fossil snails of Dallet probably lived in a humid environment, composed of shallow marshes and lake areas. A sudden flood due to a flood, a tectonic collapse or a sudden rise in water tables could have trapped these pulmonate gastropods, drowning them before quickly burying them under sediment. The absence of traces of dispersion and the preservation in a quasi-intact position reinforce this idea of rapid sedimentation, an essential condition for fossilization.

Hypothesis 2 : Volcanic activity

The geological context of the region, marked by active volcanism at the time, opens the possibility that an eruption directly caused the mass mortality. The snails could have been exposed to toxic volcanic gases, such as sulfur dioxide, or to a sudden fall of volcanic ash covering their habitat. This hypothesis is supported by the mineral composition of the fossils, indicating a strong interaction with post-eruption hydrothermal fluids.

Hypothesis 3: An extreme climatic event

Rapid climatic changes, such as a cold snap or a drought, could have caused the sudden disappearance of these snail populations. These gastropods, sensitive to variations in temperature and humidity, would have succumbed to intense environmental stress, before their shells were buried and replaced by lussatite.

Open questions and ongoing research

Despite these theories, several elements remain unexplained. Why do fossils sometimes seem aligned, as if a current had oriented them before they were buried ? Why do some layers show intact shells, while others present scattered fragments or deformed shells ? These observations suggest that the mechanisms behind this mass mortality could be multiple, combining hydrological, geological and climatic factors.

Researchers are continuing their analyses today. These efforts may one day make it possible to precisely reconstruct the last moments of these gastropods and elucidate the mystery of their sudden extinction.

Preparation of collector's items

Collectible items are particularly difficult to preserve on matrix, which makes them rare ; snails transformed into lussatite are in fact separated from the latter by a thin layer of powdered bitumen and are only attached to the matrix by the peristome. The specimens circulating on the market are therefore mostly free and devoid of matrix. There are two types of matrix for these objects. The first is a characteristic rather friable detrital horizon visually resembling peperite (a local volcanic breccia); it is in this rock that lussatite snails are the most aesthetic. Preparation most of the time involves gluing the matrix and careful removal with a needle. The second rock is a very hard siliceous limestone requiring advanced preparation methods to remove the fossils (pneumatic pencil). Some have attempted to clear and clean the samples using a sandblaster, but the results are disappointing, with the lussatite becoming matte... We have also carried out size tests on broken samples, with a rather unusual result.

References :

Collectif. (2015). La lussatite, l’opale d’Auvergne et autres trésors de la Limagne (Puy-de-Dôme). Hors-série n°21 de la revue Le Règne Minéral. Éditions du Piat, 84 pages

Brongniart, A. (1810). Mémoire sur des terrains qui paraissent avoir été formés sous l'eau douce. Journal des Mines, 27, 5-41.

Rey, P. (1965, 1966, 1968). Contributions à la paléontologie des calcaires oligocènes de la Limagne : études sur la faune des gastéropodes. Revue de Paléontologie Française.

Courville, P. (2011). Révision de la classification des gastéropodes fossiles de l’Oligocène terminal. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France.

Boivin, P. (2009). Observations sur les intercalations de pépérites dans les calcaires de la Limagne : implications pour l'hydrothermalisme et la fossilisation en lussatite. Clermont Geosciences Bulletin.

Thomas, P. (2010). Dynamique des dépôts pyroclastiques et mortalité des gastéropodes en contexte volcanique. Journal of Volcanology and Sedimentary Processes.