The history of the mineral trade

The trade in collectible minerals, distinct from the industrial exploitation of minerals for economic and technological uses, is an ancient and fascinating activity that has developed in parallel with the history of Science. From Antiquity to the present day, minerals have been prized not only for their utilitarian properties, but also for their beauty and rarity. This article traces the evolution of the trade in collectible minerals through the ages, exploring why these natural stones are so highly prized and how their trade has evolved.

Antiquity : the beginnings of mineral collecting

The history of mineral collecting dates back to Antiquity, a period during which certain stones were already highly prized for their beauty and symbolic powers. Amber, for example, extracted from the Baltic Sea, was traded as early as the Bronze Age and prized for its golden color and mysterious electrostatic properties.

In ancient Greece, Theophrastus (372-287 BC), a philosopher and naturalist, wrote one of the earliest known works on stones, entitled Peri Lithon (On Stones), in which he describes minerals not only for their physical properties, but also for their aesthetic and mystical values. Similarly, the Romans were known for their love of gems, such as rubies, emeralds, and sapphires, and for importing gemstones from distant lands such as India and Egypt.

However, minerals were not only collected for their beauty. Some minerals were also believed to have medicinal or magical properties, which gave them additional market value. Wealthy citizens of the Roman Empire or Greek nobles sometimes displayed their minerals as luxury items symbolizing their status.

Renaissance and the rise of Cabinets of Curiosities

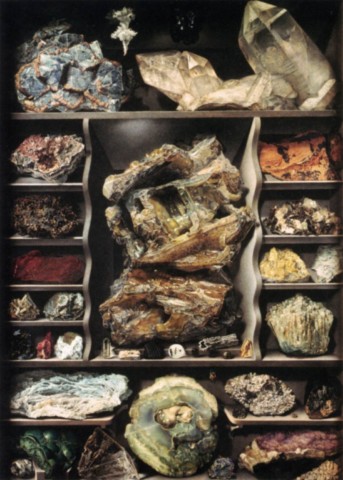

The Renaissance, beginning in the 14th century, marked a turning point in the mineral trade and collection, with the emergence of cabinets of curiosities. These private collections, which brought together natural history objects, exotic artifacts, and works of art, often included rare and spectacular minerals. European princes, kings, and scholars accumulated minerals for prestige, but also to feed their growing scientific curiosity about the natural world.

Cabinets of curiosities of this era frequently contained crystals, gems, and rare minerals imported from Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Agates, amethysts, quartz, and other stones adorned the collections of patrons and scholars. These objects became not only evidence of their owners' extensive geographical and geological knowledge, but also objects of philosophical contemplation, reflecting the beauty and harmony of nature.

Traders specializing in precious stones and rare minerals emerged at this time, traveling the world to bring back exotic specimens. The development of European maritime trade allowed the discovery of new deposits, creating a truly international market.

The age of Enlightenment and the beginnings of modern mineralogy

In the 17th and 18th centuries, mineral collecting became more systematic and scientific. With the rise of geology and mineralogy as scientific disciplines, mineral collectors evolved into amateur or professional scientists seeking to understand the properties of minerals, their chemical compositions, and how they were formed.

Figures such as Romé de l’Isle (1736-1790) and René-Just Haüy (1743-1822), considered the fathers of modern mineralogy, helped popularize the study of minerals. Together with other geologists, they collected minerals not only for their beauty, but also for their scientific characteristics, including their chemical composition and crystal structure.

During this period, mineral dealers appeared in major European cities, selling specimens to collectors, scientific institutions, and nascent museums. Increasingly sophisticated private collections emerged, often acquired by universities and museums for use as educational materials. By this time, the trade in collectible minerals was no longer confined to the noble elite, but had expanded to a wider clientele of scientists, amateur collectors, and the bourgeoisie.

19th Century : The Golden Age of mineral collecting

The 19th century was a booming time for the mineral collecting trade. With the expansion of the mining industry during the Industrial Revolution, new mineral deposits were discovered around the world, including in the United States, Russia, Australia, and South Africa. This greatly increased the availability of rare specimens and stimulated demand from private collectors and institutions.

The great international exhibitions of the 19th century, such as the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, also helped to increase interest in minerals. Mineral dealers and collectors from around the world exhibited their specimens at these events, encouraging the exchange of knowledge and trade between amateurs and scientists.

During this period, notable collectors such as Albert Heim and Friedrich Mohs built legendary collections that can still be seen in natural history museums today. The Mohs classification, introduced in 1812 to classify minerals according to their hardness, has become a reference for collectors and mineral dealers.

20th Century and the advent of international mineral trade

The 20th century saw the professionalization of the trade in collectible minerals with the emergence of mineral exchanges and international exhibitions dedicated specifically to this activity. Mineral shows such as those in Munich (Germany), Tucson (USA), and Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines (France) have become essential events for collectors, dealers and enthusiasts from all over the world.

Improved extraction and transportation techniques have allowed collectors to access even rarer and more impressive specimens. Giant quartz or calcite crystals discovered in deep cavities, as well as colorful minerals such as tourmaline from Brazil or aquamarine from Pakistan, have captivated the imagination of collectors.

At the same time, scientific advances have allowed us to better understand the structure of minerals and their physical properties. Modern analysis methods such as X-ray diffraction or SEM, introduced during the 20th century, have made it possible to identify new minerals and enrich private and public collections.

21st Century and the emergence of the Internet

With the advent of the Internet and social networks, the 21st century is marked by a major transition for the field. Indeed, the many new means of communication allow a very rapid expansion of the market. Prospectors from formerly remote areas can much more easily exchange and sell the fruits of their finds by limiting intermediaries and maximizing profits. The number of mineral exchanges exploded, television shows on the subject appeared.

In the 2010's, the trade in collectible minerals quickly became a flourishing international market, supported by a growing demand from amateurs, museums and investors. Exceptional specimens can reach record prices, such as Laurent fluorite, a red fluorite on smoky quartz discovered in the Mont Blanc Massif by Christophe Perray and sold to the Ministry of Culture for 250,000 euros.

However, these record sales, the over-publicization of the field and the proliferation of mineral fairs are not without controversy. They lead to a considerable increase in the prices of collectible minerals, which, with the help of the economic and health crises, gradually began to lose interest in them among the general public at the beginning of the 2020's. Thus, collectible minerals strictly speaking gradually gave way to polished stones and trinkets. Collectible minerals found themselves relegated to the background, once again reserved for an aging elite of specialists and became less popular in the eyes of new generations.

References :

Burek, C. V., & Higgs, B. (2007). The role of women in the history of geology. Geological Society of London.

King, R. J. (2006). Minerals Explained: The Collector’s Guide to the Mineral Kingdom. Geological Society of London.

Mottana, A., et al. (1977). Encyclopedia of Minerals. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Pagel, W. (1958). The Scientific Origins of Geology. Oxford University Press.