Emeralds from Panjshir, Afghanistan

Emeralds from the Panjshir Valley in Afghanistan are among the most fascinating gemstones in the world. Officially discovered in the 1960's, these gemstones were already mentioned in ancient writings dating back to Greco-Roman times. Located approximately 120 km north of Kabul, the Panjshir Valley has become an iconic region for emerald production since the 1980's, rivaling in quality those from the famous Muzo mine in Colombia. This article explores the history, geology, gemmological characteristics, economics and challenges of mining emeralds from Panjshir.

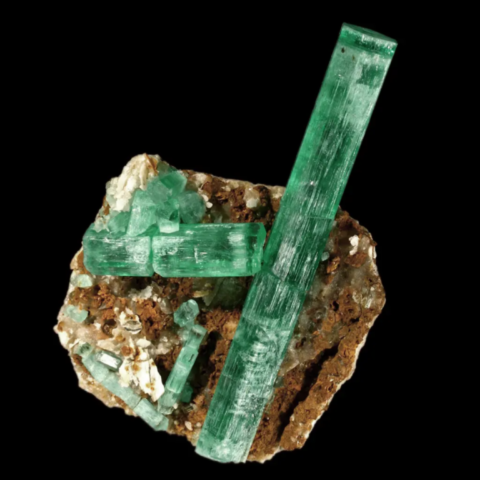

Right photo : Cluster of emerald crystals from Panjshir, Afghanistan © Rémi Bornet

A historical legacy

The history of Panjshir emeralds goes back centuries. Ancient accounts, such as those of Pliny the Elder in the 1st century AD, speak of the "Smaragdus" of Bactria, a region encompassing present-day Afghanistan. These stones were highly prized for their brilliant color and rarity. However, their scientific identification as modern emeralds was not confirmed until the 1970's, during prospecting by Soviet geologists near the village of Dest-e-Rewat.

The 1980's were marked by a rapid growth in artisanal mining, even in the midst of war. During the Soviet occupation, income from the sale of emeralds was often used to finance the Afghan resistance forces (the mujahideen). This episode made the Panjshir emeralds not only a natural treasure, but also a symbol of resilience for the local population.

Unique geology

The Panjshir Valley is located in the Hindu Kush Range, a geologically complex region formed as a result of the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. Emeralds form in fractures and shear zones. They are often associated with intense circulation of hydrothermal fluids, where they interact with igneous, metamorphic, sedimentary and evaporitic rocks. The main mining areas in the valley include Khenj, Mikeni, Buzmal and Darun. These sites are located at high altitudes, between 3000 and 4000 meters. Panjshir emeralds are always associated with shale rocks and mafic dykes containing traces of chromium and vanadium, which play a crucial role in the formation of their characteristic green color. The deposits extend over an area of approximately 20 km long and 3.2 km wide, making Panjshir one of the largest districts for this gemstone in the region.

Emeralds from the Panjshir Valley occur either as well-developed automorphic crystals or as crystal aggregates nested in veins and hydrothermal alteration zones. These crystals are associated with a wide variety of minerals. In particular, carbonates accompanied by hematite, often altered to limonite, quartz, combinations of quartz and carbonates such as dolomite or ankerite, pyrite and carbonate assemblages, as well as parageneses rich in quartz, tourmaline and carbonates are observed. These veins are always related to hydrothermal alteration processes, such as albitization or tourmalinization. Neoformations including pyrite, microcline, white mica, epidote, albite, chlorite as well as biotite or phlogopite can also be found there.

Geological map of the Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan according to Sabot & al. (2000)

Gemological characteristics

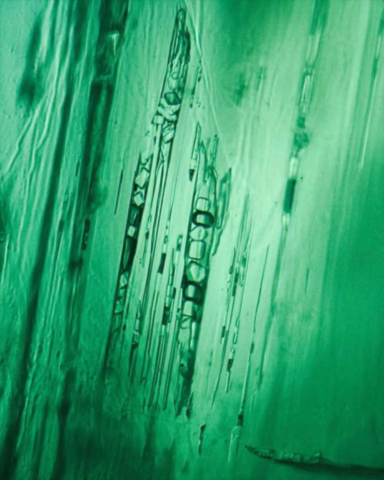

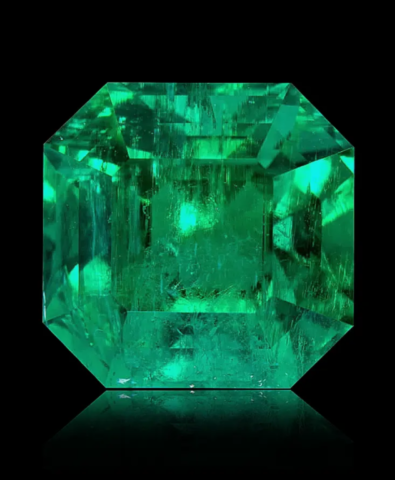

Panjshir emeralds are distinguished by their bright green color, which can rival that of Colombian emeralds. Their chemical composition shows a high content of chromium (up to 1983 ppm) and vanadium (up to 1885 ppm). This chemical combination gives the stones their brilliance and intensity of color. They often have three-phase inclusions (liquid, gas and solid crystals), which are typical of hydrothermal deposits. The oxygen and hydrogen isotopic composition of emeralds suggests a metamorphic or magmatic origin of the feeder fluids, enriched by interactions with evaporitic rocks. The fluids involved in the formation of emeralds are characterized by high salinity (up to 21-33% NaCl). These fluids probably originate from the dissolution of evaporites, a process similar to that of Colombian emeralds. The presence of liquid CO2 and crystal salts such as sylvite and halite in fluid inclusions indicates a genesis at medium temperature (400°C), resulting from complex fluid-rock interactions.

Right photo : Polyphase inclusions in an Afghan emerald © GIA

Operation and challenges

Since the 1980's, emerald mining in the Panjshir Valley has undergone a gradual transformation. While it once relied on entirely artisanal methods, it has gradually become more organized. Despite this, the majority of miners continue to use rudimentary tools, such as hammers and chisels, to work in narrow, poorly ventilated galleries. These conditions, combined with the high altitude and harsh climate, make their work particularly demanding.

The industry faces several major challenges. Due to a lack of regulation, most mines operate informally, making it difficult to manage resources and combat smuggling. Local conflicts are also a problem, as some mines are controlled by local groups or middlemen, reducing the income received directly by miners. The mountainous terrain, altitude, and lack of suitable roads and infrastructure make access to mining sites perilous. Finally, political instability, amplified since the Taliban came to power in 2021, makes the future of this industry uncertain and increases the risks of unsustainable exploitation.

Despite these many obstacles, Panjshir emeralds have captured the attention of international markets. A 2009 study estimated that the valley’s annual production represents a gross value of several tens of millions of dollars. However, this wealth rarely benefits local residents, which raises questions about the equitable redistribution of profits.

Economic importance and prospects

Panjshir emeralds represent an important economic resource for Afghanistan. They are exported mainly to markets such as Dubai, India and sometimes Europe, often under the label of Colombian emeralds. High-quality stones can fetch very high prices, sometimes exceeding $100,000 per carat for the finest.

However, the majority of transactions take place in an informal setting, evading taxes and government regulation. Formalizing the industry could transform this wealth into a sustainable source of income for the country.

Panjshir emeralds embody a unique wealth, both natural and cultural. Their beauty, equal to that of the world’s most prestigious stones, and their fascinating history make them prized gems on the global market. Yet their potential remains underexploited due to regulatory, smuggling and conflict issues.

Better management of the industry, combined with political stabilization efforts, could transform Panjshir emeralds into a pillar of economic development for Afghanistan while preserving this treasure for future generations.

References :

Bowersox, Gary & Snee, Lawrence & Foord, Eugene & Seal, Robert. (1991). Emeralds of the Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan. Gems & Gemology 27 No. 1 26-39.

DeWitt, Jessica D., Chirico, Peter G., O’Pry, Kelsey E., Bergstresser, Sarah E. (2020) Mapping the extent and methods of small-scale emerald mining in the Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan. Geocarto International

Giuliani, G. (2022). Émeraudes, tout un monde ! Éditions du Piat.

Michael S. Krzemnicki, Hao A. O. Wang and Susanne Büche (2021) A New Type of Emerald from Afghanistan’s Panjshir Valley. The Journal of Gemmology 37(5), pp. 474–495

Sabot B., Cheilletz A., De Donato P., A. Banks P., Levresse G., Barrès O. (2000) Afghan emeralds face Colombian cousins. Chronique de la Recherche Minière 541. 111-114